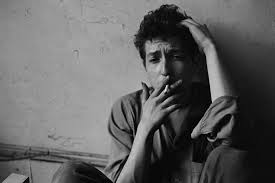

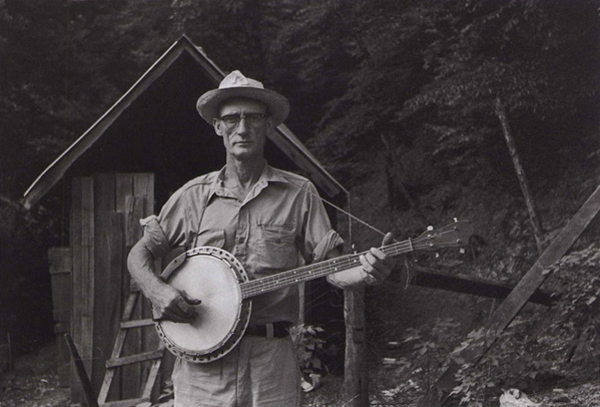

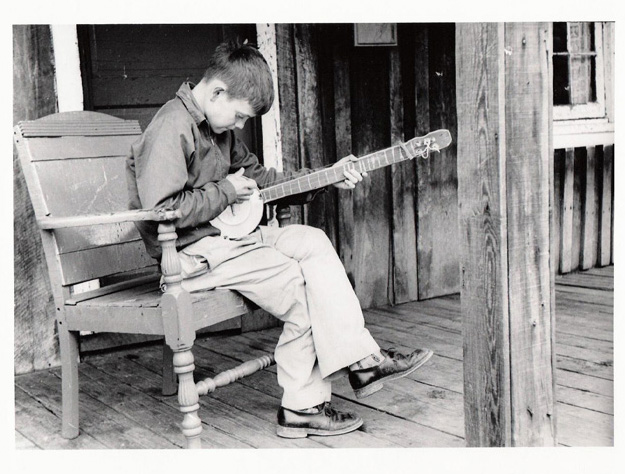

John Cohen’s photo of the great banjo player Roscoe Holcomb. (The photo can be found in Cohen’s magnificent book The High & Lonesome Sound, published by Steidl)

For ten days in February the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival took over Missoula. I had the idea that I would write a few pieces about it for a couple of magazines in London. The first article absolutely flowed onto the page. It came out of a meeting with John Cohen at the opening night of the festival. Over the next few days, while John was in town, I chatted to him between films and in lobbies of cinemas. The piece I wrote is a hard one to place. It is not a review, it is not an interview. It is a response to an artist’s work. An artist whose films moved me so much that at one Q+A I burst into tears while asking him a question. (I know, I know).

(Update: after an editor in London told me this piece was ‘unprintable’ and ‘a complete waste of time’, the Nation took it. It can be found in their June 2, 2015 issue.)

A still from John Cohen’s ‘Gypsies Sing Such Long Ballads’ (1981) — the film looks at the plight of Traveller musicians in Scotland and got me (and others) sobbing.

Here is what I wrote—and for those of you who want more information on this wonderful artist, film-maker, photographer, musician and musicologist you can go to his website or look up his films or the many records and CDs he made with the New Lost City Ramblers. In the meantime, I hope the following captures some of his spirit, intelligence, generosity and enthusiasm. I did get his blessing on this piece of writing, which means as much to me as getting it published. Thank you, John.

John Cohen with some of his photos.

John Cohen and the Lost Art of Documentary

“Can I add something to your mix?” John Cohen asks me after I tell him I am here at the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival in Missoula, Montana to write about films in the context of the American West.

“Yes, please,” I say, grateful for feedback, any feedback but particularly his.

“What is documentary?” he says and fixes me with a razor-sharp, mischievous gaze.

We are talking at the opening night party after having seen Alex Gibney’s Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief based on the book by Lawrence Wright.

“I mean, what is documentary,” he repeats with the emphasis on the ‘is’.

“I think it’s changing at the moment. In flux,” I say.

“That film tonight,” he says shaking his head, “is just so different from my films. It is so objective,” he adds. “I don’t trust objectivity.”

I ask how close he got to his subjects when he was filming Huayno musicians in Peru or Roscoe Holcomb in Kentucky or travellers in Scotland. But this is not the sort of objectivity John is talking about. He is talking about the concept of objectivity and how an audience interprets the levels of distance and closeness a director has with its subject and thus to its viewers. He was living next door to Robert Frank and the Maysles in the 50s and 60s and discussions about this very thing would have been flying around.

“I want to feel the filmmaker in the film,” he says.

“Yes,” I say and fall silent. We are at a party; the music is loud. I can’t help but feel that perhaps now that we are firmly in the age of information, documentaries have become more concerned with disseminating information than they are with sharing experience. Would anyone watch Salesman now? Would anyone make it?

The work of John Cohen, which is being celebrated at the Big Sky Film Festival, is all about experience and has nothing to do with the one-dimensional facts we have at our fingertips on our iPhones.

John points to the band, Scrapyard Lullaby, on a makeshift stage and says, “I’m going to be playing with them on Sunday Night.”

The New Lost City Ramblers with John Cohen on the far left.

It takes me a second to remember that John Cohen is eighty-two. Apart from his white hair there is nothing about him that might suggest he has lived as long as he has. I listen to Scrapyard Lullaby’s Bluegrassy music and wonder how it will feel for them to be playing with one of the founding members of the New Lost City Ramblers. Formed in 1958, the Ramblers, who included Mike Seeger and Tom Paley, ignited the old-time music revival by bringing rural vernacular music of the South to audiences whose knowledge of folk music didn’t stretch beyond Joan Baez or The Kingston Trio. Not only did the Ramblers bring the music of the people back to the people, they also managed to get some of the original performers to play live around the country. They shared the stage with the likes of Tom Ashley, the Stanley Brothers, Maybelle Carter, Elizabeth Cotton, Dock Boggs and the great banjo player Roscoe Holcomb.

Woodie Guthrie with Jack Eliot. Photo by John Cohen

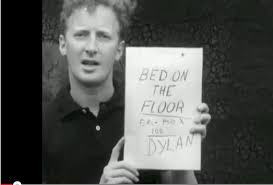

The New Lost City Ramblers were very much on the scene when a young Bob Dylan arrived in Greenwich Village from Minnesota. John told me of a clip he had found of Dylan, which he filmed on a rooftop in 1962. He was testing the camera he had just bought with his neighbour Robert Frank from the Maysles brothers in order to go off and make his first film The High Lonesome Sound. The sound recorder stopped working so he filmed Dylan as a silent actor. Over two minutes of raw footage with time code and all, Dylan in clothes reminiscent of the Kid wordlessly channels Charlie Chaplin as he tries on a variety of hats plucked from his guitar case. This is the sort of gem John Cohen seems to unearth from his vaults in Putnam County, NY.

John Cohen holding the title card to a short film he shot with Dylan on his rooftop in 1962.

Recall any photo you’ve seen of Dylan from the sixties, whether he’s smoking or not, walking down a street or sitting in a loft, and the chances are it is a John Cohen shot. Unsurprisingly Dylan has a huge amount of respect for the Lost City Ramblers. In his Chronicles, he writes,

“Everything about them appealed to me … All their songs vibrated with some dizzy, portentous truth. I’d stay with The Ramblers for days … . For me, they had originality in spades, were men of mystery on all counts. I couldn’t listen to them enough.”

My first exchange with John Cohen reverberated in me long after I got home from that party. It turned out to be the first of many rushed conversations over several days between screenings of his films and over cups of coffee in the lobby of the Wilma Theatre or sitting by the stage at the Top Hat.

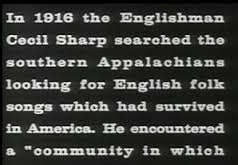

Cohen’s The High and Lonesome Sound (1963) has become a touchstone for anyone in search of musical and cinematic authenticity—the filmic equivalent to Alan Lomax’s and Harry Smith’s field recordings. Filmed in Eastern Kentucky, Cohen makes clear from the beginning that for the subjects of this film,

“Music is the celebration of the hard life … The home music and the church singing are a way of holding on to the old dignity. Music is not an escape. It gives a way of making life possible to go on. Life is hard here and music is the celebration.”

The film’s images possess and haunt: a miner, cigarette in hand, crouches into a wagon as it sends him underground to dig for coal. What looks like fog heading across the lush ancient forests is coal smoke. Children play in wheelbarrows full of coal droppings and dogs play in the background while men, smeared in soot, wander slowly home from the mines. Girls in pretty dresses skip through the grass. In the Holiness Church of God, men and women cry out and feel the Holy Spirit as it absolves them, comforts them and releases them from the pain of living. I saw Flannery O’Connor’s world come to life in The High and Lonesome Sound.

A still from one of John’s films: documentary is as much about capturing the big moments as the small ones.

As with so much of John Cohen’s work, the music of the people he films is set against the wider backdrop of politics and society. The music he captures in this film whether it be the singers in church or Roscoe Holcomb on his porch or the Shepherd Family around their dinner table is the connective tissue between the mines, the church and the people in this part of America, that in 1962 looks and feels forgotten. Towns with names like Hazard, Lynch, Viper and Defiance and lanes called Lonesome Mountain Road are captured on film, the names themselves pointing to a past and present as far from Greenwich Village as possible.

Roscoe Holcomb (1912-1981), who had not been filmed or recorded until Cohen found him, talks of his music in The High and Lonesome Sound as being spiritual—he does not use this word the way a new age seeker would, but with the meaning of touching something beyond the realm of the seen or the everyday, touching the space that joins every human on the planet. His gift for banjo-playing was God-given, he tells us,

“It is a gift and I believe God gave it to me. And I believe it enough that I’m going to let him take it.”

Roscoe Holcomb is one of the finest banjo players ever to have lived. His face is serious and thin with lines etched in a pattern of hard work, worry and sorrow—his features are reminiscent of William Burroughs drained of self-consciousness. His voice penetrates, and tells of a hard life and a deep soul. He speaks like a philosopher and sings from a place that seems almost untouchable. The songs he sings are old and yet one feels, listening to him, that there is something modern about them, something of the existential.

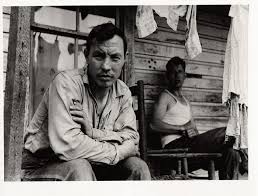

Vicco, Eastern Kentucky, 1959. (Reprinted in John Cohen’s book The High & Lonesome Sound, published by Steidl.)

The scene Cohen shot in the Holiness Church of God, in Delphia, Kentucky almost never happened Cohen says. In fact, a lot almost never happened in this film. He went to the church every Sunday for five weeks asking if he could film a service. And every Sunday he got the answer “no”. On the last day, he went to the church and told them he was leaving. “Oh c’mon in,” they said. “You’re one of us now.” Using only available light, the scenes of the service have an intimacy as if we are right there with the preacher and the men and women talking in tongues, receiving the Holy Spirit, convulsing with passion for Christ. You get the sense they were not aware of being filmed, such is Cohen’s sensitivity and ability to be in his films while being totally unobtrusive. The hand of the director is there, but it is unseen. To answer his question from the night before, “This is documentary.”

Coal miners in Eastern Kentucky. Photo by John Cohen (reprinted in his book The High & Lonesome Sound, published by Steidl)

Seven years later, Cohen made The End of an Old Song (1970) about unaccompanied ballad singers in North Carolina. One of the greatest of these musicians was Dillard Chandler (1907-1992) from the town of Sodom. The film opens inside Chandler’s simple, spartan cabin. He tells us he isn’t too lonely because every now and then he goes to town and takes a woman out and maybe keeps her for a day or two. His voice when he sings issues forth with a clarity and a longing. The isolation of these mountains is so acute that Dillard tells us his address is on Route 3, and then adds that he has no post box and has no use for mail. This is the land where people have no bank accounts, no post boxes. It is impossible to imagine in our connected age, such isolation. And yet there seems to be a link between this timeless music which speaks directly to us with its attending pain and joy and this lack of supposed ‘connection’ to an outside world. Now that we are all connected, how close are we really?

In one extraordinary scene Dillard Chandler goes out on one of his missions to find a companion for the night. He meets a dark-haired woman in a bar and they sit in a booth drinking beer and laughing with another couple. We can’t hear them but we hear Dillard in voice over saying, “All my good times are past and over”. He then stares at the juke box which is playing Merle Haggard and George Hamilton IV. “Is this the future”, we can almost hear him thinking? When his woman takes herself off to sit with another man Chandler’s face is that of a character from one of the ancient ballads he sings with such raw emotion. This is a real man, a great singer, one of the last ballad singers left. This is a document of life being lived as art.

John tells a story about being the “good little filmmaker”. When he finished The End of an Old Song he took it to North Carolina to show it to the people who were in it. The film started and John noticed Dillard Chandler still wasn’t in the audience. And then he remembered the ending of the film which shows him out on the prowl. He suddenly got very worried that he was revealing Chandler in a bad light to his community. But when Chandler talks of getting a girl for a night or two, men in the audience began shouting out, “Dillard, you tell it like it is!” This is also documentary.

Eastern Kentucky, 1959 by John Cohen (reprinted in his book The High & Lonesome Sound, published by Steidl)

After his Appalachian films, Cohen was commissioned to track down the origins of the ballads sung in North Carolina. This became Gypsies Sing Such Long Ballads (1982), shot in 1977 and 1978. I was not the only person in the audience brought to tears by this film, which in pure Cohen style seamlessly meshes the music of the people with the politics oppressing them. The ballad-singing travellers near Perth, Scotland who Cohen filmed were being re-housed “for their own good” in dingy council flats. The lives they had been living for generations seemed to be disappearing before our very eyes. The fact this was shot on film added to its melancholy nature. I felt I was witnessing not only the end of the travellers’ way of life, but the end of a way of seeing. I felt a nostalgia for the aesthetic of real film, for the texture of celluloid and its physical presence.

A scene in the Perth Housing Office, which Cohen shot from above, reduces the moustachioed official to the petty bureaucrat that he is. The travellers in this film, such as Belle Stewart, sing with such feeling, and yet many of the songs are about the lords who historically had been the ones to rule over these travellers. The movement of music from one continent to another and how songs travel is a theme running through Cohen’s work. The lines of continuity are fluid but do not always flow in expected ways.

To wrap up the weekend retrospective of his work, John Cohen got up on stage and played with the local folk string trio Scrapyard Lullaby. They did ‘Jenny Jenkins’, ‘The Girl and the Snake’ and ‘The Coo-Coo Bird’ among other traditional songs. He had told me he was going to sing a song he had written in Missoula forty years ago when he was here playing with the New Lost City Ramblers. He was here for some kind of “cultural event” (said in the tone of voice of someone who is not in favour of manufactured culture) and had been shown a church on a nearby reservation. He had said he couldn’t sing the song here all those years ago, but he felt Missoula was probably ready for it. “I liked the Indians but I hated that church,” he told me.

I agreed that Missoula would now be receptive to such a song.

John sang it unaccompanied, completely a cappella. It tells the story of how the church had been painted with holy scenes. Someone realised that the figures in the paintings were white men and women, not a native face to be seen. So a painter was brought in to add some Native Christians. How was this done? The Indians were portrayed as those writhing in pain in the flames of hell. All these years later, John’s anger is still present. He is still moved by our ability to oppress and to dismiss the voices of the disposed. Yet, this anger somehow never dominates his work. It simmers quietly away, giving his work its urgency and potency, yet what you take away from his films and from his songs is a respect for our ability to weather injustice and heartbreak.

John Cohen on stage at the Top Hat, Missoula, Montana playing with Scrapyard Lullaby, February 9, 2015.

So, what is documentary? I thought to myself after a weekend of immersing myself in his work. The man who filmed in Peru and Appalachia and Scotland was not looking to please his audience, nor was he pandering to marketing people. He was putting images and sound together in a manner that is unadorned and unadulterated. Just showing us what life is through the lens of his own experience.

At the very end of the evening someone asked John to name his favourite creative act.

“Inhaling and exhaling,” he replied without missing a beat.

Literally being alive whilst metaphorically being alive to everything around him. That seems to me what John Cohen’s work is all about: inhaling and exhaling. What more is there.

(A big thank you to Gita Saedi Kiely, the executive director of the festival, for being so generous and making all this possible.)